Farmers planting during a rainy season in Dali, North Darfur, Sudan. Photo: UN Photo / Albert Farran

In the previous module we learned that the climate crisis is a health crisis, which underscores an urgent call and implied responsibility to protect the health of current and future generations.

Facts on climate change and health impacts

Ours is an age when humanitarian disasters caused by wildfires, flooding, heatwaves and hurricanes and cyclones have become the norm.

Climate change is intensifying and prolonging extreme weather events and putting at people health at risk, including access to clean air, safe drinking water, nutritious food, and secure shelter. It also poses a significant risk of reversing the strides made in global health over several decades. It’s illogical that anyone can still deny that climate change is a direct threat to human health?

The WHO says 3.6 billion people already live in areas highly susceptible to climate change. That’s nearly half of the global population.

- Between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250 000 additional deaths per year, from undernutrition, malaria, diarrhoea and heat stress.

- Women and children are 14 times more likely to die as a result of a disaster than men and that women and girls are more likely to be malnourished than men and boys, so it is clear that climate risks are not equally shared.

- The direct damage costs to health (excluding costs in health-determining sectors such as agriculture and water and sanitation) is estimated to be between US$ 2–4 billion per year by 2030.

- Areas with weak health infrastructure – mostly in developing countries – will be the least able to cope without assistance to prepare and respond.

- Reducing emissions of greenhouse gases through better transport, food and energy choices can result in large gains for health, particularly through reduced air pollution.

As we witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic, health systems that are weak are unable to hold a line of defence against emerging threats, including the impacts of a changing climate. As journalists we need to check on government’s political will and capability to provide health care to citizens. This is a fundamental government function for which political leaders need to account.

Health systems must be able to deliver essential public health interventions during extreme events and under climate stress, and to be part of a multisectoral response to emergencies. To protect the health of populations from the effects of climate change and avoid widening health inequities, countries must build climate resilient health systems.

One Health

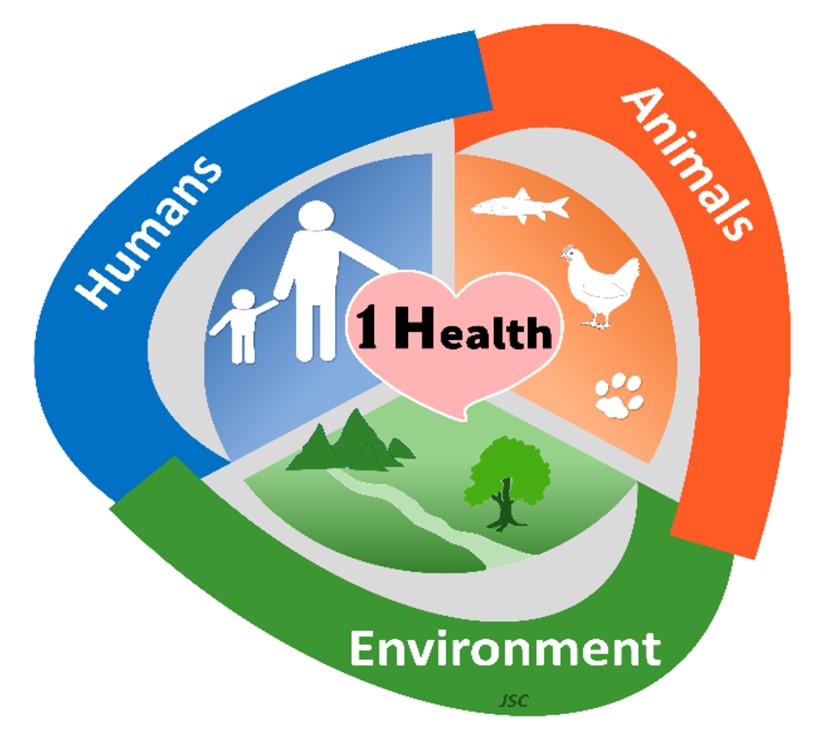

WHO is supporting countries design and implement a One Health approach which recognizes the interconnectedness of human health, animal health, and environmental health. Simply put the health of humans, animals and our environment are woven together in a bond that is inseparable, yet fragile.

The tridimensional concept of One Health. Artwork from Professor João Soares Carrola (JSC) of the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/12/8/2808

One health and the climate change link

Climate change significantly affects each of these interlinked elements, which in turn has an impact on the overall One Health framework. Here are some ways climate change impacts the One Health approach:

Human health: Climate change can directly impact human health in various ways, including heat-related illnesses, respiratory problems from air pollution, waterborne diseases from contaminated water sources, vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue fever, and mental health impacts from extreme weather events. Indirectly, climate change can worsen food insecurity and malnutrition which lead to long-term health consequences. We will explore these areas in more depth in the next section and module.

Animal health: Climate change affects the health and well-being of animals too. Changes in temperature and precipitation patterns can alter the distribution of disease vectors and pathogens, affecting the spread of infectious diseases among animals. Also, climate-related events such as droughts, floods, and wildfires can disrupt ecosystems, leading to habitat loss, changes in species distributions, and increased competition for resources among wildlife.

These changes can impact the health of both domesticated and wild animals. As of 2024, three out of four emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic in nature – meaning that they originated in animals. Human-activity driven factors such as climate change, urbanization, animal migration and trade, travel and tourism continue to influence and increase the emergence, re-emergence, distribution and patterns of zoonotic diseases.

Here is an example of how armed conflict can fuel zoonosis. In correspondence to The Lancet medical journal Yassir Adam Shuaib from the Department of Preventive Veterinary Medicine and Public Health, at the Sudan University of Science and Technology, said armed conflict in Sudan has interrupted veterinary health services, creating an environment suitable for the spread of zoonotic diseases.

Environmental health: As we saw in the previous module climate change influences environmental factors such as temperature, precipitation, air quality, water quality, and ecosystem robustness. Changes in these factors can have a domino effect on human and animal health. The WHO promotes a multidisciplinary approach as the best way for researchers and countries to tackle the effects of climate change on humans, animals and the environment. This means public health agencies, veterinary services, environmental organizations, policymakers, and communities need to work together to develop and implement strategies for climate adaptation, mitigation, and resilience-building that prioritises one health.

One Health is more than a mere buzzword

If journalists are to make a positive contribution to saving our ailing planet, the One Health approach needs to be reflected in reporting. Journalists can do this by making sure that human, animal, and environmental health questions are looked at holistically, and understanding that each element affects the other. By making the connections for our audiences we can give a more comprehensive understanding of the problem and potential solutions, rather than just a siloed approach.

Last word:

If our planet were a patient, it would be admitted to intensive care. Its vital signs are alarming. It is running a fever, with each of the last nine months the hottest on record, as we hurtle towards the 1.5 degree threshold. Its lung capacity is compromised, with the destruction of forests that absorb carbon dioxide and produce oxygen. And many of the earth’s water sources – its lifeblood – are contaminated. Most concerning of all, its condition is deteriorating rapidly. Is it any wonder, then, that human health is suffering, when the health of the planet on which we depend is in peril? — Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus WHO Director-General speaking at the 6th session of the UN Environmental Assembly in Nairobi, Kenya on 29 February 2024.

- For more on the One Health approach see this resource: https://healthjournalism.internews.org/resource/journalism-for-one-health-the-internews-approach/

- Click here for a journalists guide to reporting on the One health approach: https://earthjournalism.net/resources/a-journalists-guide-to-covering-and-implementing-the-one-health-approach-in-reporting

- Need to know more about zoonosis? This resource will fill you in. https://earthjournalism.net/resources/a-journalists-guide-to-covering-zoonotic-diseases

- Here is a WHO fact sheet on zoonosis: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/zoonoses

- This is a site worth looking at for an African perspective on One Health: https://africacdc.org/programme/surveillance-disease-intelligence/one-health/