When we think about translation, we think about changing words from one language to another.

Science has its own language, which only scientists speak – and it is often up to journalists and health advocates to translate ‘health science’ in a way that the average person can understand. It would help a lot if scientists did more to decode their speech, to use less technical terminology, or explain concepts in ways the average person can understand or relate to. Many do try to do this, and we need to nurture our relationships with those individuals and encourage the others to get on board with Research Translation.

Journalists’ biggest allies for Research Translation are civil society health advocates who spend their lives translating what science has found to make it meaningful for people who need the intervention. Advocates are also experienced in translating science into action points for policymakers – another skill that comes in handy for journalists whose job it is to hold people in powerful positions to account. By the way: non-journalists often complain that journalists have their own language too! So remember, your new scientist friend may not know what your nut graph (or graf), or fade-in or inverted pyramid or op-ed are code for – and you may have to translate for them as well!

If speakers of language X want to convey something to speakers of language Y, there are three basic approaches:

- Break it down (but don’t dumb it down) into the essential components that matter

- Use analogies, comparisons or idioms that vividly illustrate how something works, or

- Learn a new language.

We know that approach 3 is not feasible. We can’t expect all our readers, listeners and viewers – from busy moms, to Fifth Grade school learners, to retired grandparents – to learn the language of science. We must Translate it for them, through utilizing approaches 1 and 2, and with the help of scientists and health advocates.

One of AVAC’s goals is to strengthen sharing and translation of research into policies and practices to ensure support for research agendas that reflect stakeholder needs and interests. Through its programs, AVAC also builds relationships between advocates, journalists, and researchers to promote informed reporting of science. Why? Because that is how we will get to Science as Story. A journalist who is mastering Research Translation is translating science into stories that matter.

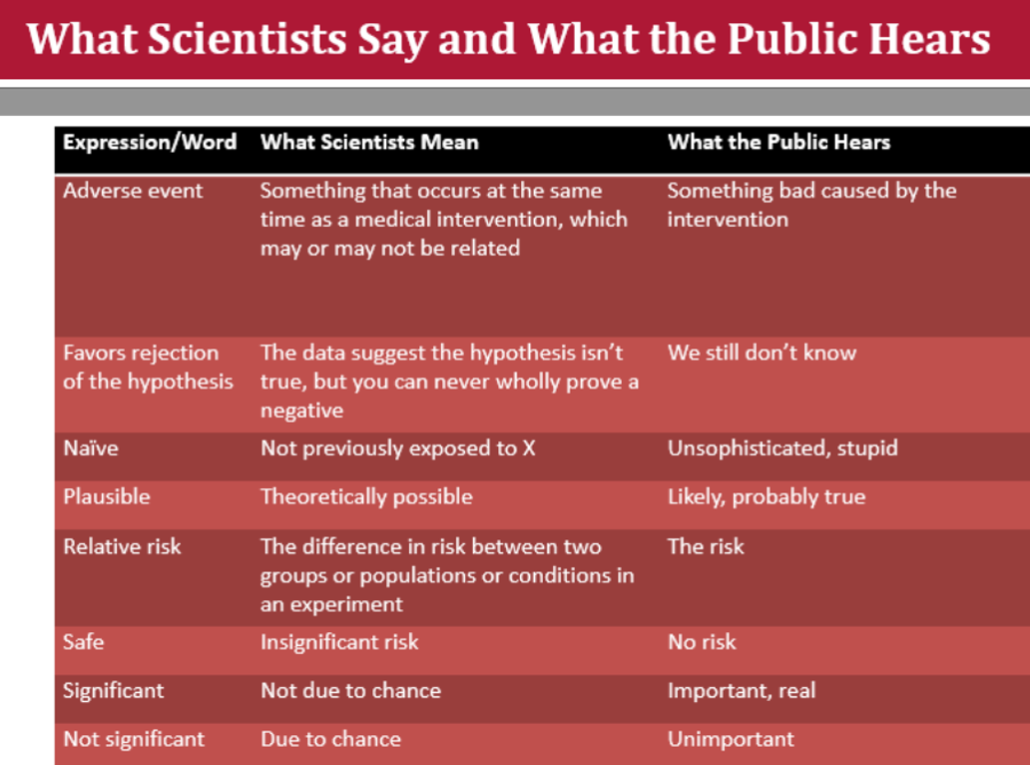

Want to see a few examples, of how scientific terms can get “lost in translation”? Check out the examples in the image below:

Read on!

These two readings are guides on how to report scientific findings:

- How to read and learn from scientific literature, even if you’re not an expert

- How to report scientific findings

This reading has an excellent round-up of terms commonly used in clinical research.

Using numbers in stories

A journalist doing Research Translation inevitably has to deal with NUMBERS!

Before moving to data journalism, the science journalist must be 100% comfortable with using numbers in stories! See how easily we use that expression “100%”? In ordinary speech, that’s ok, but in science it means something completely different.

Using numbers in reporting is important, because numbers help us to quantify things, and demonstrate the impact and/or significance of things for our audiences. But numbers can also confuse or alienate our audiences – if we do not use them appropriately, if we overwhelm by using too many numbers at once, or if we do not take care to present them in a way that clearly demonstrates their significance.

Golden rule #1: DON’T use a number if it does not add meaning to your story.

Golden rule #2: DO use a number if it helps to quantify and if it provides broader context and understanding.

- Internews has extensive experience with data journalism training and has developed a number of resources for creating effective data journalism. Take a look at the Internews Datajournalism site for more.

- There’s also the free and comprehensive Data Journalism Handbook which is well worth consulting for guidance on all aspects of data journalism.

Language

We use language to communicate – often without thinking twice. Except, as a journalist, we know that every word matters: editors ask us to write articles of a certain word count, so we have learnt how to use words economically. When we write science, we need to translate science-speak to a language that our audience understands. When we write about HIV science and the experiences of people affected by HIV, we need to take care not to add to the stigma that is holding back the end of the epidemic. We have an opportunity to change and shape norms.

The below chart offers some guidance regarding stigmatizing language we should all try to avoid using – along with preferred language alternatives we can try to use instead:

| Stigmatizing Language (“Try not to use”) |

Preferred Language (“Use this instead”) |

| HIV-infected person | Person living with HIV; PLHIV

“Person/s Living with HIV and AIDS (PLHIV)”. Never use “infected” when referring to a person. |

| HIV or AIDS patient, AIDS or HIV carrier | |

| Positives or HIVers | |

| Died of AIDS, to die of AIDS | Died of AIDS-related illness, AIDS-related complications, end-stage HIV |

| AIDS virus | HIV (AIDS is a diagnosis, not a virus; it cannot be transmitted) |

| Full-blown AIDS | There is no medical definition for this phrase; simply use the term AIDS, or Stage 3 HIV |

| HIV virus | This is redundant; simply use the term HIV |

| Zero new infections | Zero new HIV transmissions |

| HIV infections | HIV transmissions; diagnosed with HIV |

| HIV infected | Living with HIV or diagnosed with HIV |

| Number of infections | Number diagnosed with HIV; number of HIV acquisitions |

| Became infected | Contracted or acquired; diagnosed with |

| HIV-exposed infant | Infant exposed to HIV |

| Mother-to-child transmission | Vertical transmission or perinatal transmission |

| Victim, innocent victim, sufferer, contaminated, infected | Person living with HIV; survivor; warrior

Never use the term “infected” when referring to a person |

| AIDS orphans | Children orphaned by loss of parents/guardians who died of AIDS-related complications |

| AIDS test | HIV test (AIDS is a diagnosis; there is no AIDS test) |

| To catch AIDS, to contract AIDS, transmit AIDS, to catch HIV | An AIDS diagnosis; developed AIDS; to contract HIV (AIDS is a diagnosis and cannot be passed from one person to the next) |

| Compliant | Adherent |

| Prostitute or prostitution | Sex worker; sale of sexual services; transactional sex |

| Promiscuous | This is a value judgment and should be avoided. Use “multiple partners” |

| Unprotected sex | Sex without barriers or treatment-as-prevention methods

Condomless sex with PrEP Condomless sex without PrEP Condomless sex |

| Death sentence, fatal condition, or life-threatening condition | HIV is a chronic and manageable health condition as long as people are in care and treatment. |

| “Tainted” blood; “dirty” needles | Blood containing HIV; shared needles |

| Clean, as in “I am clean, are you” | Referring to yourself or others as being “clean” suggests that those living with HIV are dirty. Avoid this term. |

| A drug that prevents HIV infection | A drug that prevents the transmission of HIV |

| End HIV, End AIDS | End HIV transmission, end HIV-related deaths

Be specific: are we ending AIDS diagnoses or are we ending the transmission of HIV? |

Language matters, because it shapes perception.

A 2005 study from the International Center for Research on Women found that consequences of HIV-related stigma include:

- Loss of income

- Loss of hope

- Increased feelings of worthlessness

- Increased internalized stigma

- Poor care in the healthcare system, especially from professionals not in HIV care service delivery

- Loss of reputation in the family and community

REMEMBER that word and language associations change with time. For example, 20 years ago, the term queer was regarded as derogatory, and now it is a preferred term for queers living in certain parts of the world. Be sure to keep checking and informing yourself of the latest acceptable and non-stigmatizing language usage with regard to HIV and gender, and other social issues – because as a journalist reporting on such issues, the words you use can make a difference.